We all share a deep reverence for Scripture, but are we sometimes holding too tightly to specific words, ‘clinging to the letter. The variation in Mark 1:41, for instance, serves as a compelling example.

We love the Bible. We rightly call it the inspired, authoritative Word of God (2 Timothy 3:16–17). Yet sometimes, in our zeal to honor Scripture, we subtly shift our devotion from the living God who speaks through it to the precise wording of a particular English translation, or even a specific manuscript tradition. We begin to treat the form of the words themselves as the ultimate, unerring object of trust, rather than letting those words faithfully direct us to Christ.

The Bible wasn’t given to us as a single, dictated, unchanging modern-language text dropped from heaven. God sovereignly inspired human authors—men from different cultures, eras, and backgrounds—to write in their own languages and styles. The result is both fully human and fully divine, preserved perfectly in the original autographs.

Over centuries, as the text was copied by hand, minor variations arose: spelling differences, word order, occasional synonyms. In the New Testament alone, we have thousands of manuscripts, and while the vast majority of variants are insignificant, a few are more meaningful—like the well-known difference in Mark 1:41.

Most manuscripts say Jesus was “moved with compassion” toward the leper. A small minority reads that He was “indignant” or “angry.” Textual scholars debate the evidence carefully, but notice what doesn’t change in either reading:

Jesus touches the untouchable. He heals the man completely. His mercy and power shine forth unmistakably.

The pattern holds across the entire manuscript tradition: core doctrines—the deity of Christ, salvation by grace through faith, the resurrection—remain rock-solid and consistent in every reliable translation. The variations mostly touch on nuances that call for deeper study, not essentials of the faith.

God is not the author of confusion (1 Corinthians 14:33). Yet He permits these variations, I believe, to keep us humble. They drive us to prayer, to the Holy Spirit’s illumination, to reliable scholarship, and—crucially—to the community of the church.

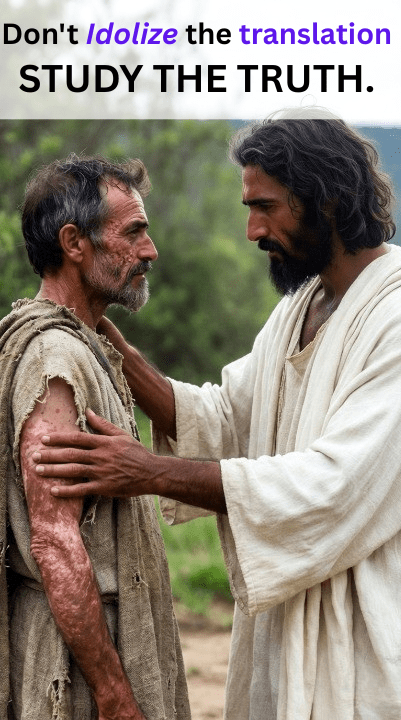

This diversity of translations and manuscripts guards against a dangerous error: elevating one English version (even a beloved one) to the status of the “perfect” Word, as if it alone were infallible. That would be bibliolatry—worshipping the book rather than the God who gave it. Scripture itself warns us: “Little children, keep yourselves from idols” (1 John 5:21). The Bible points beyond itself to the living Christ, the Word made flesh (John 1:14). As Jesus told the religious leaders, “You search the Scriptures because you think that in them you have eternal life; and it is they that bear witness about me” (John 5:39).

So here’s the helpful distinction I’ve been clinging to: There is a world of difference between confusion over core salvation truths and nuances in textual interpretation.

The gospel shines with unwavering clarity across every faithful translation: We are sinners. Christ died for our sins and rose again. Salvation is by grace through faith alone. That message is not in jeopardy.

The nuances—the precise emotion in Mark 1:41, the exact shade of meaning in a Greek verb—invite us to wrestle humbly with the text, to compare versions, to consult the church’s historic witness, and above all, to depend on the Spirit who inspired it.

My prayer is that I (and we) would never allow the precious gift of God’s written Word to become an idol in our hands. May every translation we read serve as a faithful servant, leading us to worship the living God in spirit and in truth (John 4:24).

We affirm the Bible as the authoritative Word of God, yet we must be careful not to elevate a specific translation to the status of an idol, confusing the vessel with the divine message itself. What do you think? Do you agree or disagree?