Always Reformed, Always Reforming ‘According To The Word of God’

The more I study theology, the more new words I come across, and the more I come across new words, the more I feel a need to study them to understand exactly what is meant. Not long ago, I came across the full term: ecclesia reformata, semper reformanda secundum verbum Dei—”the church reformed, always reforming according to the Word of God.”

The phrase rolls off the tongue with Reformation-day gravitas [weighty, serious, and profound nature of the Reformation]. The more I have wrestled with it, however, the more I’ve come to see a deep, underlying tension. While it seems like a straightforward call to progress, it has led to two contradictory approaches to Scripture. My aim in this short series is to unmask those two meanings and show why the difference matters more than many realize.

Two Visions of “Reforming”

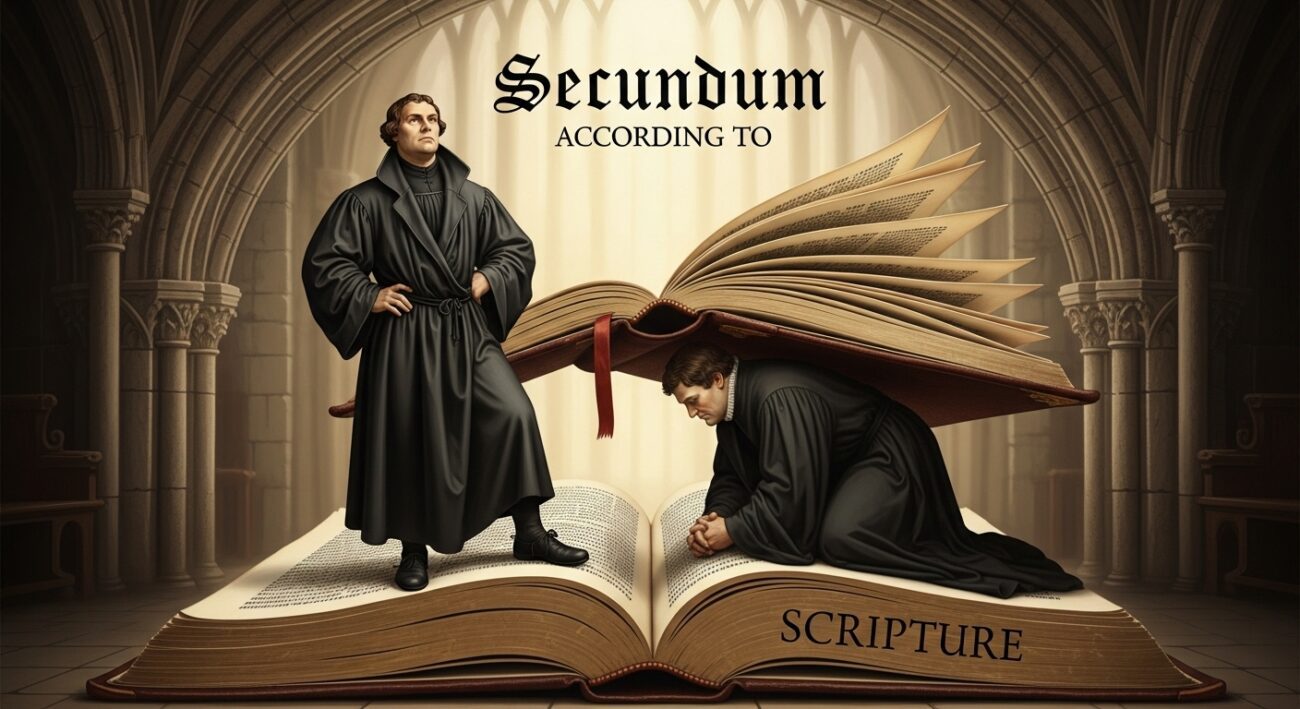

Picture two Reformers—same black Geneva gown [the traditional academic and clerical robe of the Reformation], same ESV Reformation Study Bible—yet miles apart at the level of method [the way of doing theology].

Shaper Mode (the “active” view) This Reformer sees semper reformanda as a call to continually reshape the church so that she fits the contours [the specific shape and character] of the modern world. The church, in other words, stands over Scripture, interpreting its message afresh in light of contemporary experience, science, and social consensus [a general agreement]. What is “reformed” is not, strictly speaking, the church; it is the church’s interpretation of Scripture, updated generation by generation..

For example, when a church re-evaluates a biblical command on leadership, it might appeal to a new understanding of social equality or the changing role of women in society. The argument would be that since the church has changed its mind on issues like slavery or divorce, it can also change its mind on other practices that are seen as a product of their time. This is a process similar to the Catholic system, where the church acts as the active sculptor, taking the written Word and reinterpreting it to fit the modern age. It is a process of saying, “The old way was good for its time, but now we have a deeper understanding that moves us in a different direction.” What is being “reformed” here is not the church’s submission, but its doctrine, to conform to the culture.

Shapee Mode (the “passive” view) This Reformer hears the same slogan as a summons to be re-formed—a church continually brought back under the formative pressure of the timeless Word of God. Here Scripture stands over the church, and the church’s task is one of humble submission, not creative reinvention. The reforming is something God does to the church by the Spirit speaking in the text. Here, the church is not the active sculptor; she is the clay. God, through his Holy Spirit, is the sculptor. The Spirit works by taking the tool of the written Word and pressing, molding, and shaping the church—her doctrine, her practice, and her piety—to conform to the will of God. It’s a humbling, often difficult process, but it ensures that the church does not simply invent its own way forward. For example, when the church of the Middle Ages was clinging to unbiblical traditions (like selling indulgences), the Holy Spirit used the Word of God to “re-form” the church back to the truth that salvation is by grace alone, through faith alone. This was not the church creating a new idea; it was the church being corrected by the Word of God.

Same Latin, but two antithetical [opposite or contrasting] trajectories [paths or directions]: one toward cultural adaptation, the other toward dogged submission.

Key Takeaways: What I understand So Far

Summary: Two Visions of “Reforming”

- The Problem: The phrase “ecclesia reformata, semper reformanda secundum verbum Dei” (“the church reformed, always reforming according to the Word of God“) has two opposing meanings in the church today.

- “Shaper Mode” (The Active View):

- The Church’s Role: The church acts as the active sculptor, constantly reshaping its doctrine to fit the modern world.

- Authority: The church stands over Scripture, reinterpreting it in light of contemporary experience, science, and social consensus.

- Example: When a church re-evaluates a biblical command on leadership, it might appeal to a new understanding of social equality, arguing that since the church has changed its mind on issues like slavery or divorce, it can also change its mind on practices that are seen as products of their time.

- Result: The church’s doctrine is conformed to the culture, not to the Word.

- “Shapee Mode” (The Passive View):

- The Church’s Role: The church is the clay, being molded and shaped by the Holy Spirit speaking through the Word.

- Authority: The church stands under Scripture, submitting to its timeless and unchanging authority.

- Example: When the church in the Middle Ages was selling indulgences, the Holy Spirit used the Word to “re-form” the church back to the truth that salvation is by grace alone, through faith alone. The church was corrected by the Word, not creating a new idea.

Result: The church is conformed to the Word, not to the culture.

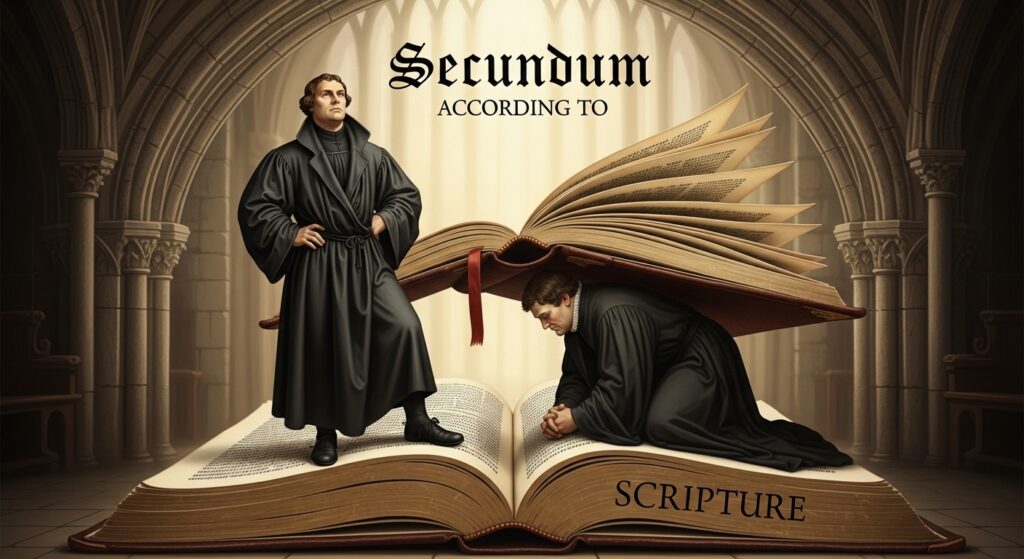

The One-Word Hinge: “Secundum”

The entire debate pivots (hinges or turns) on one tiny Latin preposition (a word that shows a relationship between other words) buried in the fuller phrase:

ecclesia reformata, semper reformanda secundum verbum Dei – “according to the Word of God.”

What does secundum (“according to”) actually imply?

For the shapers, secundum is attitudinal (based on attitude or feeling). Think of it as “in the same spirit as” or “with the same openness displayed by” the Reformers when they re-examined medieval tradition. The content of Scripture is honored, but its application is ever negotiable (open to discussion and change), always provisional (intended to be temporary or open to revision).

For example, egalitarianism, the view that men and women have equal authority and should serve in all the same roles in the church, is often justified by a “Shaper” approach. The argument re-examines biblical commands on leadership, like those in 1 Timothy, and reinterprets them through the lens of modern social equality. Similarly, the New Perspective on Paul (NPP) is a perfect example of this. It argues that the Reformers misunderstood the Apostle Paul and that a “fresher” reading of the text is required. It claims that “works of the law” are not moral strivings but ethnic boundary markers, thereby redefining the very nature of justification. In this view, the church acts as the active sculptor, taking the written Word and reinterpreting it to fit the modern age. It is a process of saying, “The old way was good for its time, but now we have a deeper understanding that moves us in a different direction.”

For the shapees, secundum is normative (establishing a standard or rule). It signals the standard by which every doctrine, practice, and polity (form of government or organization) must be measured and, when necessary, corrected. “According to” means “brought into conformity with” the fixed deposit of God’s revealed truth.

For example, the Reformers did not challenge the Catholic Church’s authority so they could invent new doctrines. They challenged it because the Church’s doctrines had drifted away from the Bible. The Reformers were saying, “We are not trying to stand over the text, as the Catholic system does, but we are standing under it. We are not creating new truths; we are simply being corrected by the unchanging truth of God’s Word.” A modern example of this is the late Dr. R.C. Sproul. Throughout his ministry, he consistently argued that the church must not conform to the changing trends of the world. He was known for his firm, uncompromising commitment to the authority of Scripture and the confessions that faithfully summarize its teaching. He called the church to return to the foundational truths of the Reformation, not as a way of being “stuck in the past,” but as a way of being corrected by the Word of God for the sake of the Gospel’s purity. This was not the church creating a new idea; it was the church being corrected by the Word of God.

One preposition, two hermeneutical galaxies (two entirely different ways of interpreting the Bible).

Key Takeaways

Summary: The Two Meanings of “According To”

- “Shaper” Mode: The church acts as the active sculptor, reshaping doctrine to fit the modern world.

- Authority: The church stands over Scripture.

- Example: Using modern social equality to reinterpret biblical commands on leadership or redefining justification through the New Perspective on Paul (NPP).

- “Shapee” Mode: The church is the clay, being molded and shaped by the Holy Spirit speaking through the Word.

- Authority: The church stands under Scripture.

- Example: Dr. R.C. Sproul’s call to return to the unchanging truths of the Reformation for the sake of the Gospel’s purity.

Standing Over vs. Standing Under

So the divide is not merely semantic (related to the meaning of words); it is ecclesiological (related to the doctrine of the church) and, ultimately, doxological (related to the worship of God).

Standing over the text turns the church into a theological entrepreneur (someone who organizes and operates a business saying “make it better, make it greater, make it more appealing, market is ready and open for change’), mining Scripture for adaptable principles while reserving the right to relativize (to make something’s value or validity depend on its relationship to something else) anything that feels culturally antiquated. The result is a church that evolves—sometimes dramatically—under the pressure of each new “present age.”

This is where we see the slow but sure drift back toward a system of authority similar to the Roman Catholic Church. While not as explicit as the Catholic Magisterium, the “Shaper” view makes the church’s leadership the ultimate arbiter of truth. We see this in movements like “Evangelicals and Catholics Together” (ECT), a 1994 document that sought unity at the cost of the very doctrines that separated the Reformation from the Catholic Church.

A similar trend is evident in the Convergence Movement, which attempts to blend evangelical, charismatic, and liturgical forms of worship, often downplaying doctrinal differences for the sake of unity. More broadly, this approach is seen in the “new ecumenism” of the 21st century, where dialogue between different Christian traditions is often focused on social issues, shared values, and spiritual experiences rather than on the core theological disagreements that still separate them. This shift can sometimes be at the expense of sola Scriptura and other Reformation principles.

Standing under the text places the church in the posture of a disciple, always on the receiving end of divine address. Here “reformation” is not progress away from the past but repentance back to the Word. What is re-formed is not the gospel but the church—again and again—until she conforms to the gospel.

These tabs below provide a detailed biblical defence against the often misused comparisons to justify changing the church’s position.

In a world that continually redefines itself, the question of whether a modern church remains faithful to its historic, confessional moorings is more pressing than ever. A recent ordination, featuring the laying on of hands for women elders, raises this very concern, compelling a look back at the Westminster Confession of Faith (WCF) and the principles that shaped it. Should the divines who penned that document stand before such a service, one can only imagine their consternation, witnessing what they might view as a dangerous drift from the Word of God and the Confession they so carefully crafted.

The “Big Tent” and the Problem of Selective Subscription

The first and most fundamental point of departure is confessional integrity.The Westminster Standards and the broader biblical and confessional tradition explicitly restrict the office of elder to men. To simultaneously ordain women and claim adherence to this document raises a profound question about the nature of confessional subscription itself. Subscribing to a confession means submitting to all its doctrines, not merely those we deem fundamental or convenient. This act forces one to conclude that either the candidates do not fully understand the Confession or that the eldership has re-defined “fundamental doctrines” to exclude the passages on male eldership, such as 1 Timothy 2:12-14. Both conclusions are schismatic, quietly moving clear Scriptural commands into a category of adiaphora—a liberty of conscience that the Confession itself warns against.

Furthermore, the very act of ordination, the laying on of hands, is not a mere blessing but a solemn invocation of Christ’s authority to set apart individuals for office. The Scottish Directory for Public Worship (1645) explicitly limits this act to lawfully called men. By performing this ritual for women, the eldership is not only acting ultra vires but is also implicating every elder who lays on hands in the defiance of Christ’s apostolic order. This is a far cry from the practice of the Scottish Covenanters, who were willing to separate from their parishes rather than submit to Prelacy, demonstrating that genuine Reformed obedience often requires separation, not compromise or an “agreement to disagree.”

Finally, the concerns extend beyond church government and into the very worship of God. The regulative principle of worship (WCF 21.1) states that only what God commands in His Word is to be used in worship. The inclusion of music from movements like Bethel and Hillsong—which originate from a prophetic movement claiming ongoing revelation and which often deny penal substitution—is a direct violation of this principle. The source and theological baggage of such music are reasons for its disqualification, regardless of whether a few lines may seem orthodox. An eldership, by embracing this “Top-40 of apostate movements,” is not regulating worship according to Scripture but is instead allowing a theological drift that misleads the congregation.

In conclusion, the Westminster Confession of Faith provides a framework rooted in the sufficiency and clarity of Scripture, which the office of elder is a key part of. The evidence suggests a concerning redefinition of what it means to be Reformed—a new slogan of “always reforming” that is no longer a return to Scripture but an accommodation to culture. This path has serious implications, and as and as a matter of confessional integrity, silence on these issues often equals approval. Ultimately, the question remains: how can a minister simultaneously ordain women and claim to be “under the Word”?

Another common argument is that if the church can be flexible on divorce, it can be flexible on other matters like women’s roles. However, this is a profound misunderstanding of Jesus’s teaching. In Matthew 19:9, Jesus is not relaxing a rule; He is establishing a stricter one, pointing back to God’s original design for marriage as a lifelong covenant. The exception for divorce due to sexual immorality is a narrow one that acknowledges a violation of that covenant, but it is not a broad permission for divorce. There is no parallel here to justify changing God’s design for church leadership.

Some try to justify women in eldership by comparing the debate to past cultural practices, such as dress codes. They point to fringe groups that once argued against things like braided hair, jewelry, or certain clothing, citing 1 Timothy 2:9. Yet, this comparison fails to recognize a crucial distinction. The instructions in 1 Timothy 2:9 were likely given to prevent ostentatious displays of wealth that caused division within the church. These are matters of wisdom and cultural application. In contrast, 1 Timothy 2:12 is a direct command tied to the created order of Adam and Eve. It is a specific instruction regarding a function within the church, not a general cultural rule. To argue that human rules don’t bring piety and therefore Paul’s teachings are just human rules is to ignore that Paul, as an apostle, was inspired by the Holy Spirit. As 2 Timothy 3:16 states, “All Scripture is God-breathed.” The Bible, not flawed human reasoning, must be our guide.

The claim that the church can change its position on eldership because it changed its view on slavery is a flawed comparison. While the church in many eras has tolerated and even defended slavery, the New Testament’s treatment of it was always to humanize and ultimately undermine the practice, not to affirm it as a divinely ordained institution. For instance, in Ephesians 6:5-9, Paul instructs both masters and slaves to act justly and compassionately. It is intellectually dishonest to equate the church’s eventual, biblically-rooted rejection of slavery with a desire to overturn a direct apostolic command concerning church leadership.

Key Takeaways

- Standing Over: The church acts like a business, interpreting Scripture to fit modern principles. This leads to the church conforming to the culture.

- Standing Under: The church acts like a disciple, submitting to the Word. This leads to the church being corrected by the Word.

Next blog, hopefully in a week or two (Lord willing) we’ll dig into concrete case studies—women’s ordination, same-sex relationships, and the doctrine of hell—to see how the two meanings play out in real time. For now, let us at least agree on this: if we want to be semper reformanda, we must decide according to whom—or what—we are willing to be re-formed.

Stay tuned. God bless from Jason